Climate change is a catastrophe for humans and the environment. We have already left the ‘safe operating space for humanity’, and scientists are debating whether we have passed the 1.5°C climate threshold, the limit agreed upon in the Paris Agreement to avoid the worst and irreversible climate risks. On the face of it, the solutions seem fairly straightforward: decarbonise to stop global warming, sequester carbon to reduce carbon dioxide levels in the atmosphere, rewild to reverse species extinction.

However, when breaking into the complexity of each subset of problems, one oftentimes encounters highly interconnected dilemmas. Or, using the words of Timothée Parrique, economist at Lund University, achieving sustainability is like trying to solve a Rubik’s cube. Solving one side is necessary but not enough, and trying to solve the other five sides could mix up the colours you’ve already figured out.

Achieving sustainability is like trying to solve a Rubik’s cube.

Tomothée Parrique, economist at Lund University

The extraction of so-called critical raw materials needed for today’s renewable energy technologies is an example of such a dilemma. For instance, wind farms, solar panels, or batteries currently require non-renewable minerals such as nickel, manganese, cobalt, and lithium. Paradoxically, replacing fossil fuels with renewable energy to achieve sustainability requires mining, a process with problematic environmental and social impacts. Excessive land and water use, air and groundwater pollution, deforestation, loss of biodiversity, and soil contamination are frequently accompanied by labour exploitation, displacement, and loss of traditional livelihoods. This is why critics prefer to call renewable technologies ‘low carbon’. They also point to the extractive paradigm underpinning a green transition that doesn’t fundamentally question our society’s energy-intensive consumption and production patterns.

Europe on the move to ‘critical’ raw materials

Beyond the sustainability concerns of this form of ‘green’ extractivism, geopolitical competition for dominance in the low-carbon technology market has increased significantly in recent years. During the Covid-19 pandemic and following the outbreak of the Russian-Ukrainian war, European countries have become increasingly aware of the vulnerability of their supply chains. Efforts to increase strategic autonomy in vulnerable sectors, including the low carbon technology market, have therefore gained new momentum. The recent leap in green industrial policy in the US with the Inflation Reduction Act and China’s strong market position have provided an additional wake-up call for the EU to actively improve its position in the low carbon technologies market as well as its access to critical raw materials.

In March 2023, the EU therefore put forward the EU Critical Raw Materials Act (EU CRMA) which sets out four strategic objectives to secure the supply of so-called critical and strategic raw materials, defined in an updated list published in the Act. These materials are not only important for low carbon technologies, but also for the digital, space, and military sectors. Proposed by the Commission in March 2023, the Act has galloped through the EU’s decision-making procedures and is currently close to adoption.

In fact, it is based on a long-term EU raw materials policy consisting of legally non-binding policy documents from 2008 onwards. However, the new Act represents a major turning point as first binding act of law, which means that it will be immediately applicable across all member states once adopted. It also sets benchmarks for sourcing, processing, and recycling capacities, including a domestic sourcing target of at least 10% of the EU’s annual consumption. These objectives will be achieved by leveraging financial and legislative resources to accelerate strategic projects identified inside and outside the EU.

Picking the ‘green’ dilemma apart

The Act has been criticised by civil society, arguing that addressing the climate crisis cannot and should not rely solely on increased extraction given its environmental impacts. This adds to recent projections that global resource extraction levels are will increase by 60% by 2060 compared to 2020 levels, a worrying trend to which the EU CRMA would certainly contribute.

However, it is crucial to understand that only some of these extracted materials are destined for low carbon technologies. Other industrial and consumer uses, such as electronics, generally outweigh climate-relevant applications. The assumption that the mining industry’s interests overlap with society’s need to decarbonise must therefore be critically questioned, as must the idea that projected increases in mining are directly correlated with the expansion of low carbon technologies. Furthermore, the end use of renewable energy – powering public transport or a private fleet of SUVs – also influences how much mining we actually need to achieve sustainability. But how can we challenge powerful industries and find a democratic solution to the ‘green’ mining dilemma?

The assumption that the mining industry’s interests overlap with society’s need to decarbonise must therefore be critically questioned.

As mentioned above, the expansion of critical minerals extraction in Europe is one of the EU CRMA’s objectives. During my research, I wondered whether onshoring mining would indeed also onshore conflicts to Europe. Could bringing ‘green’ extractivism to our doorstep be a wake-up call for us, confronting us with the consequences of our imperial mode of living? And given that Europeans generally enjoy stronger civil and political rights than communities elsewhere, is it possible that such conflicts could also trigger transformative change? Or would these conflicts result in a form of NIMBYism, calling for the continued offshoring of harmful extractivism to other parts of the world?

Analyzing mining conflicts on European grounds

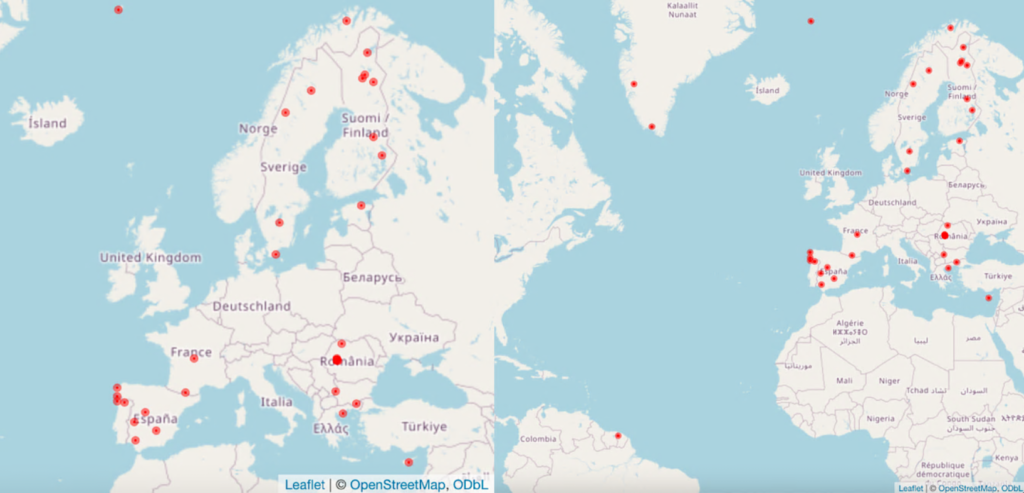

I set out to investigate this question and analysed 36 conflicts related to ‘green’ extractivism in order to understand how anti-mining groups politicise extractive projects. To do so, I used the Environmental Justice Atlas, a database documenting ecological distribution conflicts across the globe. Because the EU CRMA will be applied beyond the EU, conflicts in neighbouring countries and overseas territories were also included.

Through a thematic analysis of each conflict entry, I identified different paradigms that groups used to frame the problem of mining in their community and their opposition to mining. The experienced or expected impacts of mining were the key driver for mobilising people (impacts of mining). Secondly, the unequal distribution of the burdens of mining such as pollution, loss of landscape, loss of livelihood, and the benefits, such as revenue, were important catalysts (distributional injustice). There are two dimensions to this: the public/private divide, where private companies would unfairly profit from the exploitation of land previously owned by the public or individuals; and geographical inequalities, in the form of intra-European tensions, where the periphery is more heavily affected than the core regions.

It is noticeable that many conflicts have occurred in the Nordic region. This might indicate the Nordic countries’ enthusiasm for enabling ‘green’ extractivism on their territory, as the Finnish, Swedish and Norwegian governments aim to be at the forefront of ‘green’ and sustainable mining in Europe.

Thirdly, procedural injustice intensified mining resistance. In particular, the role of the state has contributed to politicisation. Usually appearing as an opponent of anti-mining activists, the state can sometimes also act as a supporter of their cause. Most states are more or less consistently aligned with the interests of mining companies, adopting policies that support their business models while obstructing local community participation in decision-making. Yet, they may also side with critics through environmental legislation, for example. Such contradictions imbued concerns about mining with leverage and legitimacy, while also fueling frustration with public bodies that were seen as institutions failing to fulfill their role of representing people’s interests (ambiguous role of the state).

Lastly, the incompatibility of ‘green’ mining objectives with other values such as traditional livelihoods, indigenous values, and community ties to the land contributed to politicisation (conflicting values).

How to strengthen anti-mining movements

Many, but not all actors clearly situate the conflicts they are involved in and the respective ‘green’ mining projects within a broader critique of ‘green’ capitalism, extractivism, and the ever-growing resource use footprint of modern societies. It is therefore not yet possible to draw generalising conclusions on the transformative potential of European anti-mining movements. They do not yet operate within a unified understanding of the underlying causes and solutions for their struggle.

However, with strategic visions being developed by various actors across Europe and globally, this might change soon. A key concept here is sufficiency, which aims to meet the basic needs of all without exceeding unsustainable levels of consumption and production, as defined by planetary boundaries. Justice is central to sufficiency, as it calls for a reduction in the over-consumption of energy and resources in the Global North to allow the South to develop.

Anti-mining movements should build broad coalitions around the idea of sufficiency to fight the mining boom taking place in the name of growing energy demand.

The idea of sufficiency has been widely popularised by, among others, Kate Raworth’s Doughnut Economics. It is increasingly gaining traction among policymakers, such as in the aforementioned Global Resources Outlook 2024, the IPCC’s Sixth Assessment Report, or the German Advisory Council on the Environment.

Anti-mining movements in Europe must therefore take advantage of this recent trend. They should intensify building broad coalitions around the idea of sufficiency to fight the mining boom taking place in the name of growing energy demand. One example of such strategic action is the call by 75 European organisations to integrate sufficiency measures into the new EU Strategic Agenda 2024-2029. Beyond the policy level, activists and campaigners need to understand how they can integrate sufficiency into just transition frameworks to mobilise the working population.

Sufficiency and economic democracy have the potential to bring society much closer to minimising the harms of extractive industries while reducing global warming. Both the absolute reduction in energy and material use and the provision of low carbon energy are necessary to address this challenge. There is momentum, there are solutions, now we need to continue to build political power to put people and the environment before profit.

Hannah Rebecca O'Neill

Hannah O’Neill is a PhD candidate at the Environmental Research Institute, University College Cork, researching transformative pathways to sustainability at the intersection of economics, politics, and technology beyond growth, and trying to stay true to her passion for climate utopias, eco-anarchism, and degrowth. She recently completed her master’s degree in Social-ecological Economics and Policy at Vienna University of Economics and Business, writing her thesis on the political ecology of onshoring ‘green’ extractivism to Europe.