So, here I stand. Pointer in one hand, notes with insights from our case study on lithium-ion batteries in the other hand. The presence of a functional battery in the pointer shimmers through the red dot. Gavin Bridge, my dear and esteemed colleague, is eloquently kicking off our presentation. We sketch three moments of articulation in lithium-ion-battery production from our collaborative work published in 2022 and 2023. With this short presentation, we feed into the industrial perspective on lithium, the production side of a global economy account, using the conceptual-analytical framework of global production networks (GPN). The presentation is crafted to speak to the theme of the public closing conference of the Green Dealings project and the two-day workshop ‘Governing Batteries? Articulating People and Places along Supply Chains’: It seeks to articulate the intersection of industrial policy and environmental governance.

The production bias

The GPN framework informing our work, has clear boundaries: it is production-biased; in other words, it sets out with an understanding of economic activities solely centred around the production of goods and delivery of services. GPN has little if no regard for economic activities in the sphere of social reproduction such as practices and processes that involve care, and include activities (paid and unpaid) in communities that are, in principle, oriented towards the welfare of citizens. This production bias involves dualistic thinking that subordinates social reproduction to production – production/social reproduction – by positioning activities of firms, the leading firms in a particular industry, front and centre in exploring uneven development. Why does this matter?

It matters because the GPN framework belongs to a literature family that includes commodity and global value chains (GVCs) which is drawn upon in policy circles to develop normative guidance and to offer policy advice to governments. This includes reports such as the World Development Report by the World Bank Group and publication formats of other supranational institutions including the ILO, UNCTAD, the WIPO or the WTO.

Let this be clear: It is a significant advance from conventional economic theory to have these conceptual-analytical frameworks inform policy-making as they are able to address questions of unevenness, of power and governance. Yet, there is more to be done: With a production bias in these frameworks, policy advise prioritizes production and favours the integration of local productive activity into global production.

This bias also means activities in the social reproduction sphere are considered as social and environmental dimensions impacted by production. This is highly problematic: only activities that have a price are considered, while other time-intense activities such as subsistence activities or care are not counted – they are of no value. Simply put, this makes price a measure of value (see, for example the works of Mariana Mazzucato or Marilyn Waring), and elevates price-based production for exchange in ‘the market’ above other forms and organization of economic activities such as the sphere of social reproduction, and the state.

Business as usual?

This (self)reflection revives focus on this significant ‘other’ absent in GPN accounts: the sphere of social reproduction. This sphere co-exists with (commercial) production, nourishes the social fabric and reproduces social and material life. It involves activities in households, and in communities, and – beyond consumption – plays an equally important role in the transformation of nature, for example through education.

This is the complex, entangled world of social formation – involving gender, race and class – the adult population tries to make sense of, to introduce and explain to, and hand over to the young. It may not be novel to explore the production-bias, yet foregrounding this bias and identifying alternative spaces and foci is arguably very much needed in current times shattered by multiple crises and wars.

These are times, in which disarmament efforts make way for reiterated commitments to meet agreed military expenditures to defence arrangements such as of NATO, and broader geopolitical tensions; times, in which production at industrial scale is reinvigorated with claims of green industrialization – gigafactories for battery production mushrooming, and e-mobility rolling out relentlessly; times, in which the social fabric benefits, suffers and notes ambivalences from technological advances; times, in which information technologies play a central role, connecting people across the world while at the same time isolating them, meeting needs and creating wants, and enabling silos for political polarization.

These developments drive the transformation of nature with the continuous scaling up of industrial production. They are clear imprints of the production bias. Beyond meeting human needs, limitless production serves to sustain a notion of progress. At a time when Earth’s capacity is overused, how can such production bias be maintained?

Making resources, remaking life

The transformation of nature is being accelerated by a powerful blend of institutional forecasts (such as of the IEA or the World Bank Group), economic policy and climate targets. This cocktail turns to research, development, and innovation to create moments of creative destruction with new battery chemistries substituting mineral elements. Lithium is the protagonist in electrical energy storage. Nature is transformed to reproduce the built environment.

Reproduction in this (self)reflection looks far beyond child-rearing. It is not separate from industrial production. Reproduction is about making resources, and about the socio-technical imaginaries that shape this process. It is a process imbued with power inequalities that silences some narratives and offers platforms to others.

Feminist scholars of global production come to mind for having pointed to work, labour and the role of gender, race and class in reproducing uneven patterns of activity in what is termed ‘economic development’. As researcher, I ask: What is the societal cost of silencing some voices to reproduce the same old patterns of resource-making? What is the societal cost of a political-economic model that rewards streamlining diversity, imposing dominance over co-existence, and discounting what cannot be quantitatively measured? What is the promise of lithium in this context? What can lithium tell us about the making of resources for the reproduction of life?

The concept of (re)production

Within (feminist) economic geography, a diverse range of concepts coexist in the term ‘the reproduction of life’: social reproduction, or the reproduction of materiality, and of capital, and its mode of accumulation. Yet, a constructive conversation between these different understandings is notably absent.

With few exceptions, much of what is known today about lithium suggests repeating patterns of resource-making that draw on socio-technical imaginaries with historical roots: the transformation of nature as input for industrial production; the motor of economic activity captured in discourses on green extractivism; resource extraction for capital accumulation; nature as a gift to capital.

As Cristobal Bonelli, Marina Weinberg and Pablo Ampuero Ruiz point out, lithium is also a (de)stabilizer, bringing to the table time(s), multiverses, and mental health. Lithium may reproduce uneven patterns of development, such as found in building an Ecological Civilization in and beyond China, and it may be part of off-sites of lithium production.

Reproducing life is as much about acknowledging, valuing and respecting co-existence in an ethics of care as it is about sociotechnical transitions, system transformations, and multi-scalar developments. Any account of resources that are to sustain lives with energy and materials will need to respond to questions of care and representation.

Who is part of the conversation, who is not, and why? The transformation of nature within planetary boundaries has limits, and so does any economic model based on growth.

The life of batteries, or batteries in life

I turn to the black mass in my part of the presentation. Black mass describes the product emerging from processing the shredded end-of-life battery, some of it may be reused, some not, depending on what is considered of value. I think of Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing’s The Mushroom at the End of the World. As human beings with a Western mindset framed by modernity, we are metabolizing nature at fast pace and destroying the basis of multi-species life, making batteries to continuously energize activities, without a break. Tsing points to the end of capitalist progress, the ecological devastation, and the collaborative survival within multispecies landscapes, a life in ruins such as by the matsutake mushroom commanding highest prices as a delicacy in Japan.

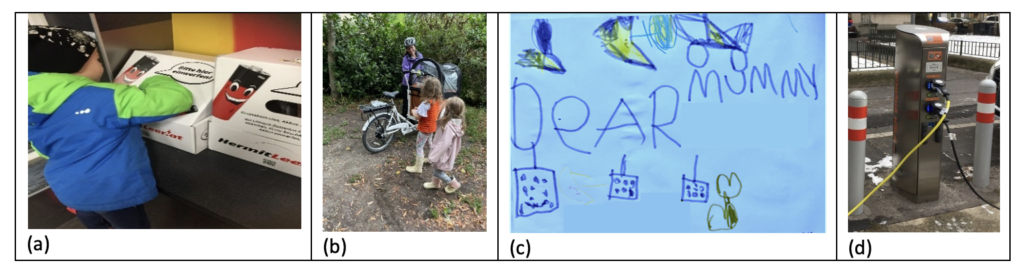

I also recall the excitement of my five-year old about the battery collection box in the supermarket: It is immediately valuable to my child as a treasure chest to fish out batteries that wait to be recycled (figure 1a). This single moment is enmeshed in social reproduction when I recall in our presentation the challenging negotiations that seek to protect the environment. I recite EU legislative targets for particular mineral elements – cobalt, lead, lithium and nickel – in the new EU Battery Directive. And I recall the question my five-year old asked me the night before departing to the workshop: Mummy, which question do you ask [in your research]?

So far, I have painted the canvas that my child was born with, with an understanding of my research as connected to nature and materials, and as focused on batteries. We find batteries in his remote-controlled car, in my laptop, mobile phone, or in the e-bike we ride to kindergarten (figure 1b). He likes to add batteries in drones to this account (figure 1c), sometimes robots. We have not yet discussed the role of battery technology in non-civil use applications. We have approached discussions about the usefulness of batteries in electric tooth brushes. We have also discussed how cables, chargers, transformers and charging stations obscure the energy used in e-cars, or e-bikes (figure 1d).

We may ask if this resource-making with lithium justifies uses of water at sites of extraction that may put local human and ecological life at risk. I am keenly pointing out to him that we have choices to make within constraints, the smaller and wider bandwidths demarcated by individual circumstances within collective conditions. These choices need to be made responsibly, whether they concern resource-making in research, such as in material synthesis, or whether they unearth lithium-bearing rocks or desalinate brine in open pools for industrial production and consumption.

The limitations of choice

I am part of lithium-ion battery production. I use batteries for communication, work and mobility, and I have come to research them. I am aware of my privilege to choose – to some extent – my relationship with lithium. This/my choice may stand in stark contrast to relationships with lithium imposed on others. Such relationships may involve, for example, uneven power relations expressed through various capital fractions of actors. It may transpire through diverging interests, represented by different weights.

So, as a mum and researcher (among other), I respond to my five-year old with a question: how do we decide about the materials we need, make, and use? How do we decide on the use of lithium in developing materials? Responsible research and innovation in the transformation of nature for the reproduction of life. Questions within my bandwidth.

Figure 1. (a) Fishing for batteries at battery collection point; (b) e-bike with lithium-ion battery under rear rack; (c) drawing of battery-operated remote-controlled snowmobile, drone, and race car; (d) e-car charging station in use.

Acknowledgements

I like to gratefully acknowledge the careful engagement with this reflection and thank Gavin Bridge and Jonas Köppel for their insightful comments. They have sharpened my perspective on the points I like to, and hopefully have, convey(ed). I also like to thank Melisa Escosteguy and Felix Dorn for facilitating the peer review process, and all organizers and contributors to the Green dealings workshop and final conference for having created, and shaped a warm and trusted environment for discussions of a variety of perspectives on lithium. The formal and informal conversations have been very valuable to my self-reflection.

Erika Faigen

Erika Faigen is an economic geographer concerned with the role of R&D and innovation in sustainable mineral-based material uses in energy technologies for global energy system transformations. She is currently a Marie Skłodowska-Curie Fellow at the University of Vienna. Erika earned her PhD in Geography at the University of Copenhagen, in collaboration with the Geological Survey of Denmark and Greenland (GEUS). She conducted research at the GEUS Centre for Minerals and Materials, and postdoctoral research with Monash University and Durham University.