The birth of a literary project, and in this case of a translation, is far from being a light one. The project can slowly journey for years as an unconscious afterthought, or, as in the case of the forthcoming publication of a series of essays (Parikka 2021), it erupts suddenly, imposing itself in the immediacy of a moment, or a place.

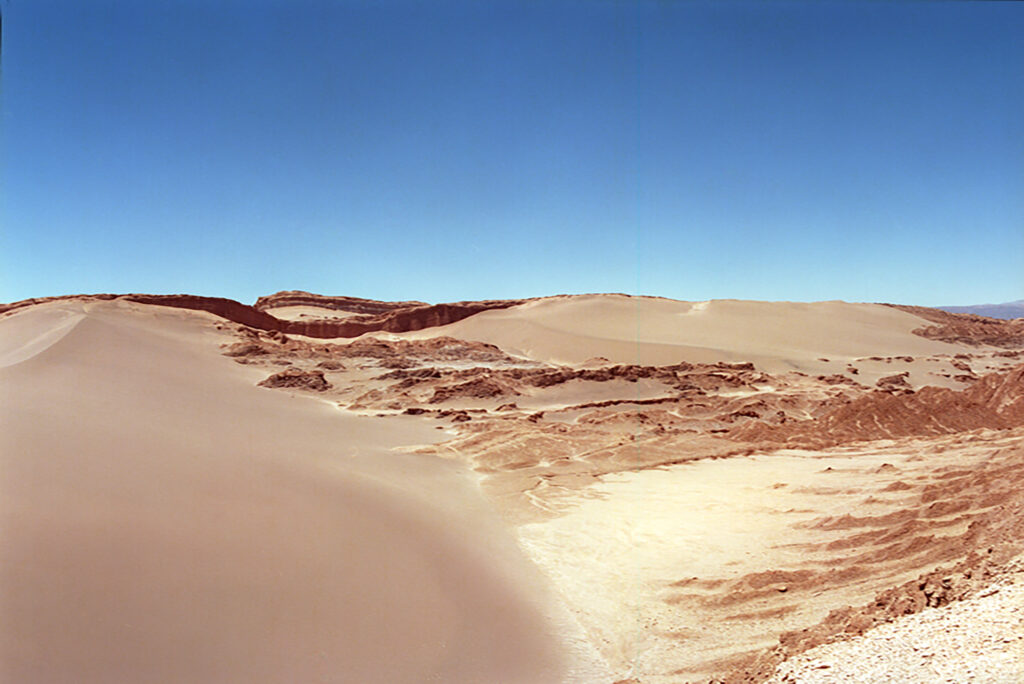

The Atacama desert is one of those rare places on earth where who we are and what we are up to, are radically transformed. I went to the North of Chile in October 2019, for a residency organised by La Wayaka Current, an artist-curator duo, who organise residencies in South America. A few kilometres away from San Pedro de Atacama, artists, curators and writers live among local communities to explore environmental issues. The connections between artists and the landscape form a peculiar bond at the intersection of socio-economical terrains and artistic methodologies.

Embedded among local populations and cultures, artists are offered a privileged access to the complex issues of what could be summed up by the vague title of Arts of Anthropocene which have been multiplying during the past decades. Though, a more critical filter would not miss that La Wayaka Current’s residency, as well as the load of artist open calls in relation to ecological issues, that are flooding specialised artist networks’ websites, are generating new forms of artistic tinged tourism of artists in residence. Experiencing far away cultures, through the filter of an art practice while simultaneously staying in dramatic and picturesque landscapes becomes the ultimate elitist form of tourism, reactivating the long historical legacy of colonial appropriation and in the case of artists, the reframing of foreign communities and cultures within western art canons.

I spent a full month in the oasis settlement, with two ceramists from Arizona and London, a poet from Malta, a performer from Seattle, two multi-media artists from Toronto and the East Coast of America, a Berlin based painter, an Alaskan photographer, and a Belgian film maker. I had brought with me Jussi Parikka’s short essay “A Slow Contemporary Violence: Damaged Environments of Technological Culture”, published in 2016. Atacama is known for its vast lithium resources, which are in growing demand due to the batteries that run the technological devices we invite into our everyday lives. The desert’s vast and immersive space disrupts the perception of time. Nevertheless, the alien dimension of the Atacama desert, as well as its extreme exoticism, are a lure. within the vast expanses of the plateau, our modernity is shaped. The desert lies at the core of our technological and media life, as our endless desires for friction-less and wireless modes of consumption and connection have come to depend on it.

Parikka is a leading theorist writing on media archeology. His interdisciplinary approach bridges philosophy with cultural and media theory. His influential essays on media history (Parikka 2012), also explore tangential angles, such as the curious Insect Media, published in 2010. In the essay I brought to Atacama, Parikka addresses the contemporary condition by exploring how technological media depend on natural resources, thereby leaving a material impact on the globe. Damaged ecosystems have come to define the Anthropocene. In his essay, he explores how, since the early 19th century, sciences and industries have excavated the earth’s underground to sustain media and wars. Starting from early discoveries in geology during the Enlightenment, he ends on the ongoing race for the rare earths that are fueling our green economy. While reading the essay, it became difficult to disconnect the landscape in Atacama from technologies.

The settlement where I stayed, comfortably nested under the canopy of local desert chañar trees, offered the most precious of all: shadow, lower temperature, and water. Water resources are managed through ancient irrigation networks that go back to pre-Inca civilisation. For centuries, lama breeding and agriculture practices have provided for desert communities in one of the most precarious ecosystems on earth, known for its scarcity of rain and its record high temperatures.

One hundred kilometres south, two mining corporations (SQM and Albemarle Corp) extract lithium from the salars. The landscape cannot be more antithetic to that of the oasis. The flat expanses of the desert are scattered with large water evaporation pools, hardly visible from the road. There is not a single tree, not a patch of grass, just sand, and dust and lithium salars. They require vast quantities of water which are obtained by tapping in the desert’s hydrological network.

In The Anthrobscene, Jussi Parikka recalls how Chile’s geopolitical role during WWI shaped technologies and media, constituting one of those entanglements that have become an epitome of our contemporary condition. The British army used its new telegraph technology to block Chilean nitrate exports to Germany. Haber and Bosch’s German corporations recalibrated the chemical short comings and instead used synthetic ammonia to produce ammunition. Parikka underlines the extent to which technology is part of war and logistics, thus engendering specific landscapes that are morphed through resource extraction and trade.

Our technologies, such as GPS, mobile phones, or virtual reality equipment, are attuned to a broad techno-scientific-military program. The Chilean desert exemplifies the deterritorialised relation between our cloud-based, wireless information technologies and the material and physical milieu where lithium is mined in remote geographies.

Even though the Cold War appears far away now, it still lingers in the subtle manners that have moved away from ostentatious manifestations of architectural remains. Minerals and materialities not only inform wars, they tell the story of “the war [that] never ended, [a war that] facilitated an entry of new sorts of technical forms of control, regulation, production of chemicals and more – an apt theme considering we are living in a sort of a continuous Cold War defined by territorial claims, energy wars, realpolitik of terrorism entangled with geopolitics, movements of biomass that expresses itself as the human suffering of forced refugee movements” (Virilio 1967, p. 15).

The text offers an insight into alternative forms of violence, what Rob Nixon in his eponymous essay names “slow violence” (2011). Mineral extraction, resource pillage, and the destruction of ecosystems generate forms of violence that require to create a new visual and conceptual grammar that is capable of making these visible. These slow violences occur at thresholds that escape human senses, at speeds that are so slow they evade our comprehension.

The burden of invisibility shadows the history of Chile. In his documentary film “Nostalgia for the Light” (2010), Patricio Guzmàn tells how the desert was used by the Pinochet regime to dump the bodies of political opponents from airplanes. The desert was used to obliterate their death as well as their corpses. But as the film demonstrates, the desert is paradoxically a space of remembrance and preservation.

The trope of visibility connects with lithium. The mineral enters media technology as a glass and ceramic component for the screens of our mobile phones that have produced a civilisation saturated with images. Parikka’s essay teases our attention back to the materialities that enter media technology, and to what he considers the environmental histories of media materiality. Media culture externalises the human senses of hearing and seeing, but it also reaches out for “light, energy, materials, minerals and more” which depend on the “geophysical minerals and energies necessary to run high-tech computational processes that constitute this other sort of planetary level” (Parikka 2016, p. 22).

Extractive industries constitute the core of the Chilean economy. They are also the engine of transformation towards what Anna Tsing in her essay “The Mushroom at the End of the World” names “capitalist ruins”, those eco-systems of a damaged planet that have come to constitute the elegiac background of our contemporary life. Toxic landscapes are remnants of geographies where waste, pollution, contamination and resource-deprived milieus are forever transformed. The Atacama desert is part of a similar slow continuous violence. It is scrutinised, and studied, and discussed, but it is progressively depleted.

This is where our bunch of artists intervene again. Geographers and theorists who research the Anthropocene geographies require methodologies and mediations that entice visibility to processes of destruction and transformation. Deep time, scattered spaces, invisible process and conceptual changes are now the common language of artists’ pieces. The Anthropocene, writes Parikka, is deeply sensorial, and artists through data visualisation, allegories, visual practices and phenomenological methodologies have developed an aesthetics for our damaged world.

“Unknown Fields Division”, a London based artists collective, is interesting in this regard. In 2015, they investigated Bolivia’s lithium fields. Their artistic project, writes Parikka, creates: “another layer of geopolitical importance through the measurability of sites by way of computational and sensorial means” (Ibid. p. 34). To render lithium more visible, the group unpacked trade data, uncovering how lithium is indexed on global commodity markets and depends on concrete supply lines of materials. By doing so, the project revealed the existence of a whole invisible network of design and architecture, that operates at different scales and evades human cognitive apprehension.

Dust never really settles in the desert. The whitish powder covered my shoes, my books, my computer. Some of that dust is still lodged deep in the back cover of Parikka’s book. I brought back dust, as well as the translation of Parikka’s essay. Infinitesimal, nearly invisible, but felt by touch, dust is a reminder of how the geological intersects “at multiple scales with entangled times, even histories; issues of technology that mobilize metals, minerals and the earth in most concrete ways” (Ibid p. 39).

References

Parikka, J. (2021): L’Antrobscène et autres violences. Trois Essais sur l’écologie des medias. Translation from English, Agnès Villette, T&P WorkUnit, Paris. The book will be published in September 2021.

Parikka, J. (2016): A Slow Contemporary Violence. Damaged Environments of Technological Culture, Published in partnership with Aarhus Art Museum and The Contemporary Condition Research Project at Aarhus University. New York.

Parikka, J. (2015): What is Media Archeology? London: Wiley.

Parikka, J. (2015): A Geology of Media. Minneapolis: University of Minneapolis.

Virilio, P. (1967): Bunker Archéologie. Paris: Editions Galilée.

About the author

Agnès Villette is a photographer whose practice is research-based and multi-disciplinary. She explores photography, texts and film to create installations that reflect upon ecological and political issues. Influenced by the theoretical writing generated by the Anthropocene, she develops projects that merge art and science. Currently she is a PhD candidate at the Winchester School of Art, University of Southampton.