In Argentina environmental information related to mining projects is supposed to be public and freely accessible. Two national laws establish this principle, one on free access to public environmental information and the other on the right of access to public information. They constitutionally oblige provincial authorities to guarantee this right to civil society. In Salta the Secretary of Mining is the agency in charge of sharing this information upon request.

On March 16, 2020, I went to the Secretary of Mining front office to submit a request asking for access to the impact assessment of Salta’s lithium projects. In this request I explained that my inquiry was motivated by the research I was conducting for my doctoral thesis and made a commitment to use the information for scientific purposes only. The administrative staff received the document, but cautioned that, given the sanitary situation caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, they could not guarantee a positive answer to my request.

Months passed and in July, when the sanitary situation allowed it, I returned to the offices to check the status of my request. The staff had no record of my application, and told me that it had probably not been processed. They recommended me to resubmit it.

On July 31, 2020, I submitted a second request. But it was not until November that I heard about my application, through a friend who happened to be working temporarily at the Secretary of Mining. He informed me that it was still in the front office. At that time I was a bit frustrated with the situation and my friend told me to try to establish direct contact with Salta’s Secretary of Mining, Ricardo Alonso. He suggested to try to “convince them”, by explaining that I would use the information only for my research.

“Try to get your superior to talk to Ricardo Alonso… it is the only way for your request to be attended to. I see here every day how requests for information are received and only those that he personally attends to are processed.”

Having failed to speak directly with the Secretary, I decided to try the official way again. On November 26, I returned to the offices, with a new request and regained hope. Upon arrival I met a security officer in a small checkpoint that was sheltering him from the intense heat. He was dressed in a black uniform and a badge on his right shoulder said “police officer of the Province of Salta”. When I tried to get in, he asked for my personal information and told me that I was not authorized to enter the place. By orders of his superiors, he told me, it was forbidden for anyone not wearing formal clothes to enter the Secretary of Mining. “To enter you have to wear a shirt or a plain t-shirt, jeans or dress pants, you cannot enter this public agency the way you are dressed”.

I was perplexed by his reaction but tried to convince him of the importance of visit. Annoyed and somewhat nervous, the police officer told me that if I tried to enter despite his warning, I would be arrested. Meanwhile, with a contemptuous expression, he asked me some questions:

“Where do you come from? How old are you? Don’t you understand what I am telling you?”

At that moment a vehicle approached. A woman got out of and asked the police officer what was going on. After a brief exchange of words, she told him to allow me in. That is how, after having suffered an act of discrimination and violence, I was able to enter and submit a new request: my third request for access to public environmental information.

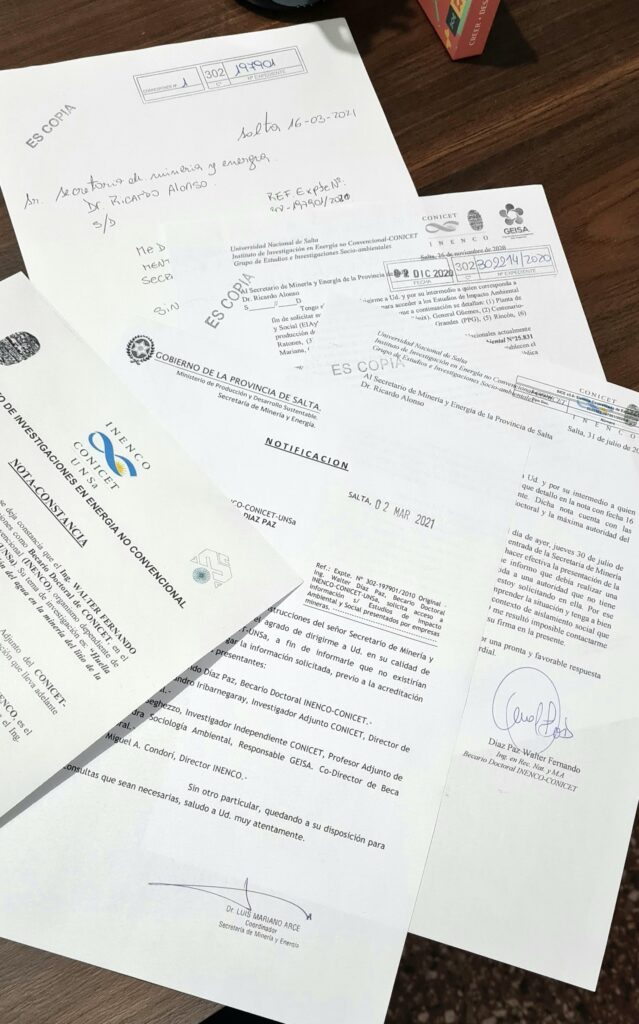

Finally, this request was processed by the secretariat’s lawyers, who responded to my request prepared on March 2, 2021. They authorized the access to the impact assessments, as long as I can prove my position as a scholarship holder with CONICET (National Council of Scientific and Technical Research) as well as the academic positions of my advisors.

On March 16, 2021, I submitted the required documentation and waited for the final approval. I have grown tired of the bureaucratic procedures and am beginning to believe that these attitudes may be an attempt to obstruct access to the requested information.

I have asked to speak to the lawyer in charge of processing the file to speed up the bureaucratic process that I have been trying to overcome for more than a year now. Showing me an official resolution and speaking in a defensive tone, he excused himself:

“Besides the fact that the information you are asking for is public, this provincial agency has its own rules. If you don’t know them, I have a copy here for you. Here we have the obligation that whoever requests information must prove his identity, otherwise the information will not be available. If you want to access the information you will have to comply with each of the legal requirements that this institution demands, whether you are from civil society, university or CONICET. Once you submit the requested information you will have to wait for us to prepare the final report.”

As I write these lines, on April 12, 2021, I am still waiting for the secretariat to comply with national law and respect my rights as a citizen. This experience got me thinking about the role of the Salta province in promoting mining projects. While the province is becoming one of the most promising destination for lithium investments, it is deliberately handing our natural resources to private companies.

The institutional violence committed against me throughout the last year led me to write down my experience. I want to seek justice and show the mismanagement of the provincial public administration. My duty as a scholarship holder of a national public organization is to generate local scientific knowledge that allows us to improve our living conditions. It is the duty of Salta’s mining secretariat to control and ensure a sustainable use of mineral resources.

Yet, can lithium mining promote sustainable development if it fosters this kind of attitude? What is the duty of the public officials working in this public agency? To serve society, ensure transparency, and inform about decision making? Or do they rather function as a sort of service that the Argentine State offers to mining companies to facilitate their negotiations, and their abuses of local communities living in the places of extraction? What role do the mining companies play in the mining secretariat’s decisions? What identity is required to prove to the agency to obtain the requested information? Is our identity as citizens not enough?

About the author

Walter Fernando Diaz Paz is a PhD student in Natural Sciences and a scholarship holder with the National Council of Scientific and Technical Research of Argentina (CONICET). He conducts research on the water footprint of lithium mining and on just energy transitions.